Baynard's Castle on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Baynard's Castle refers to buildings on two neighbouring sites in the

notes

on Stow's text.

The lord of Castle Baynard appears to have had held a special place among the nobility of London. Robert Fitzwalter explicitly retained all the franchises and privileges associated with the lordship of Baynard when he made the sale. He claimed them in 1303, his son Robert tried again before the King's Justices in 1327 and his brother John FitzWalter tried again in 1347 in front of the

The lord of Castle Baynard appears to have had held a special place among the nobility of London. Robert Fitzwalter explicitly retained all the franchises and privileges associated with the lordship of Baynard when he made the sale. He claimed them in 1303, his son Robert tried again before the King's Justices in 1327 and his brother John FitzWalter tried again in 1347 in front of the

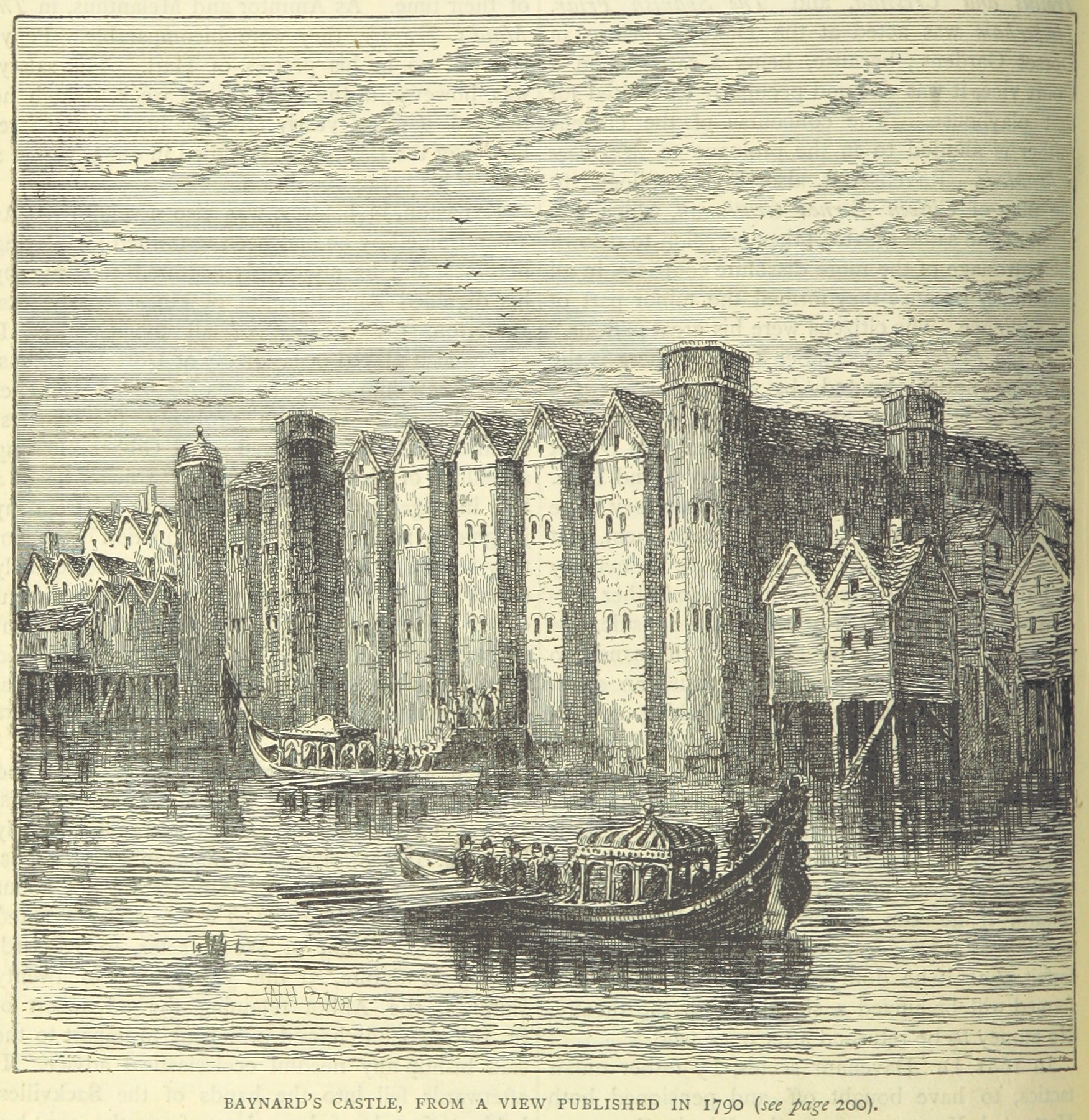

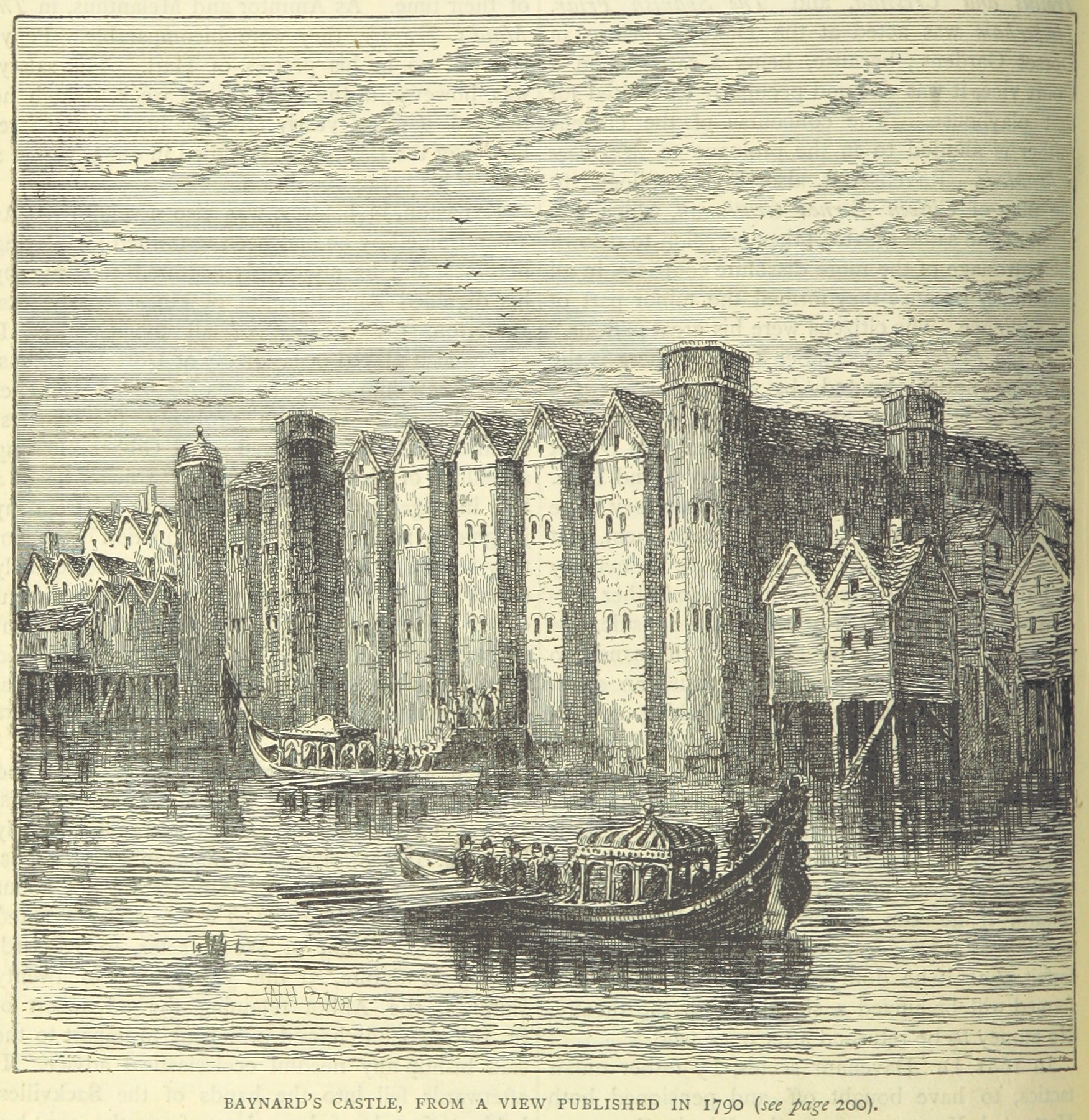

In 1501 King Henry VII "repayred or rather new builded this house, not imbattoled, or so strongly fortified castle like, but farre more beautiful and commodious for the entertainement of any prince or greate estate" (Stow). Henry's alterations included five projecting towers between two existing polygonal corner towers on the river-front. Henry stayed at the castle when attending functions at

In 1501 King Henry VII "repayred or rather new builded this house, not imbattoled, or so strongly fortified castle like, but farre more beautiful and commodious for the entertainement of any prince or greate estate" (Stow). Henry's alterations included five projecting towers between two existing polygonal corner towers on the river-front. Henry stayed at the castle when attending functions at

Baynard's Castle was destroyed in the

Baynard's Castle was destroyed in the  In the 1970s the area was redeveloped, with the construction of the Blackfriars underpass and a Brutalist office block named " Baynard House", occupied by the telephone company

In the 1970s the area was redeveloped, with the construction of the Blackfriars underpass and a Brutalist office block named " Baynard House", occupied by the telephone company

London Archaeological Archive

for more details of excavations.

City of London

The City of London is a city, ceremonial county and local government district that contains the historic centre and constitutes, alongside Canary Wharf, the primary central business district (CBD) of London. It constituted most of London fr ...

, between where Blackfriars station and St Paul's Cathedral

St Paul's Cathedral is an Anglican cathedral in London and is the seat of the Bishop of London. The cathedral serves as the mother church of the Diocese of London. It is on Ludgate Hill at the highest point of the City of London and is a Grad ...

now stand. The first was a Norman

Norman or Normans may refer to:

Ethnic and cultural identity

* The Normans, a people partly descended from Norse Vikings who settled in the territory of Normandy in France in the 10th and 11th centuries

** People or things connected with the Norm ...

fortification constructed by Ralph Baynard ( 1086), 1st feudal baron of Little Dunmow

Little Dunmow is a village situated in rural Essex, England, in the vale of the River Chelmer about east-southeast of the town of Great Dunmow. It can be reached from the Dunmow South exit of the A120 by following the road towards Braintree (B ...

in Essex

Essex () is a county in the East of England. One of the home counties, it borders Suffolk and Cambridgeshire to the north, the North Sea to the east, Hertfordshire to the west, Kent across the estuary of the River Thames to the south, and G ...

, and was demolished by King John

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Secon ...

in 1213. The second was a medieval palace built a short distance to the south-east and later extended, but mostly destroyed in the Great Fire of London

The Great Fire of London was a major conflagration that swept through central London from Sunday 2 September to Thursday 6 September 1666, gutting the medieval City of London inside the old Roman city wall, while also extending past the ...

in 1666. According to Sir Walter Besant

Sir Walter Besant (14 August 1836 – 9 June 1901) was an English novelist and historian. William Henry Besant was his brother, and another brother, Frank, was the husband of Annie Besant.

Early life and education

The son of wine merchant Will ...

, "There was no house in ondonmore interesting than this".

The original castle was built at the point where the old Roman walls and River Fleet

The River Fleet is the largest of London's subterranean rivers, all of which today contain foul water for treatment. Its headwaters are two streams on Hampstead Heath, each of which was dammed into a series of ponds—the Hampstead Ponds an ...

met the River Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the The Isis, River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the Longest rivers of the United Kingdom, se ...

, just east of what is now Blackfriars Station. The Norman castle stood for over a century before being demolished by King John

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Secon ...

in 1213. It appears to have been rebuilt after the Barons' Revolt, but the site was sold in 1276 to form the precinct of the great Blackfriars' Monastery.

About a century later, a new mansion was constructed on land that had been reclaimed from the Thames, south-east of the first castle. The house was rebuilt after 1428, and became the London headquarters of the House of York

The House of York was a cadet branch of the English royal House of Plantagenet. Three of its members became kings of England in the late 15th century. The House of York descended in the male line from Edmund of Langley, 1st Duke of York, ...

during the Wars of the Roses

The Wars of the Roses (1455–1487), known at the time and for more than a century after as the Civil Wars, were a series of civil wars fought over control of the English throne in the mid-to-late fifteenth century. These wars were fought bet ...

. The accession of King Edward IV was proclaimed in the castle.

The house was reconstructed as a royal palace by King Henry VII (1485–1509) at the end of the 15th century, and his son Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is best known for his six marriages, and for his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disa ...

gave it to Catherine of Aragon

Catherine of Aragon (also spelt as Katherine, ; 16 December 1485 – 7 January 1536) was Queen of England as the first wife of King Henry VIII from their marriage on 11 June 1509 until their annulment on 23 May 1533. She was previously ...

on the eve of their wedding. In 1551, after Henry's death in 1547 and during the reign of the infant King Edward VI, the house was granted to Earl of Pembroke

Earl of Pembroke is a title in the Peerage of England that was first created in the 12th century by King Stephen of England. The title, which is associated with Pembroke, Pembrokeshire in West Wales, has been recreated ten times from its origin ...

(1501–1570), brother-in-law of Henry's widow, Queen Catherine Parr

Catherine Parr (sometimes alternatively spelled Katherine, Katheryn, Kateryn, or Katharine; 1512 – 5 September 1548) was Queen of England and Ireland as the last of the six wives of King Henry VIII from their marriage on 12 July 1543 until ...

. Pembroke built a large extension around a second courtyard in about 1551. The Herbert family took the side of Parliament in the English Civil War

The English Civil War (1642–1651) was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Parliamentarians (" Roundheads") and Royalists led by Charles I ("Cavaliers"), mainly over the manner of England's governance and issues of re ...

, and after the 1660 Restoration of the Monarchy the house was occupied by Francis Talbot, 11th Earl of Shrewsbury

Francis Talbot, 11th Earl of Shrewsbury, 11th Earl of Waterford (1623 – 16 March 1668), was an English peer who was a Royalist officer in the English Civil War. He survived the war only to be mortally wounded in a duel with the Duke of Bucking ...

, a Royalist

A royalist supports a particular monarch as head of state for a particular kingdom, or of a particular dynastic claim. In the abstract, this position is royalism. It is distinct from monarchism, which advocates a monarchical system of governme ...

. Baynard's Castle was left in ruins after the Great Fire of London

The Great Fire of London was a major conflagration that swept through central London from Sunday 2 September to Thursday 6 September 1666, gutting the medieval City of London inside the old Roman city wall, while also extending past the ...

in 1666, although fragments survived into the 19th century. The site is now occupied by a BT office called Baynard House and the castle is commemorated by Castle Baynard Street and the Castle Baynard Ward

Castle Baynard is one of the 25 wards of the City of London, the historic and financial centre of London.

Features

The ward covers an irregularly shaped area, sometimes likened to a tuning fork, bounded on the east by the wards of Queenhith ...

of the City of London.

Norman castle

Today theRiver Fleet

The River Fleet is the largest of London's subterranean rivers, all of which today contain foul water for treatment. Its headwaters are two streams on Hampstead Heath, each of which was dammed into a series of ponds—the Hampstead Ponds an ...

has been reduced to a trickle in a culvert under New Bridge Street that emerges under Blackfriars Bridge

Blackfriars Bridge is a road and foot traffic bridge over the River Thames in London, between Waterloo Bridge and Blackfriars Railway Bridge, carrying the A201 road. The north end is in the City of London near the Inns of Court and Temple Ch ...

, but before the modern development of London it was the largest river in the area after the Thames. It formed the western boundary of the Roman city of London and the strategic importance of the junction of the Fleet and the Thames means that the area was probably fortified from early times.

Richard of Cirencester

Richard of Cirencester ( la, Ricardus de Cirencestria; before 1340–1400) was a cleric and minor historian of the Benedictine abbey at Westminster. He was highly famed in the 18th and 19th century as the author of '' The Description of Britain'' b ...

suggests that King Canute

Cnut (; ang, Cnut cyning; non, Knútr inn ríki ; or , no, Knut den mektige, sv, Knut den Store. died 12 November 1035), also known as Cnut the Great and Canute, was King of England from 1016, King of Denmark from 1018, and King of Norway ...

spent Christmas at such a fort in 1017, where he had Eadric Streona

Eadric Streona (died 1017) was Ealdorman of Mercia from 1007 until he was killed by King Cnut. Eadric was given the epithet "Streona" (translated as "The Acquisitive”) in Hemming's Cartulary because he appropriated church land and funds for ...

executed.Page (1923), p. 138 Some accounts claim this was triggered by an argument over a game of chess; Historian William Page suggests that Eadric held the fort as Ealdorman of Mercia

Earl of Mercia was a title in the late Anglo-Saxon, Anglo-Danish, and early Anglo-Norman period in England. During this period the earldom covered the lands of the old Kingdom of Mercia in the English Midlands.

First governed by ealdormen under t ...

and after his death it may have been granted to Osgod Clapa Osgod Clapa (died 1054), also Osgot, was a nobleman in Anglo-Saxon England during the reigns of Kings Cnut the Great, Harold Harefoot, Harthacnut, and Edward the Confessor. His name comes from the Old Danish Asgot, the byname Clapa meaning coarse, o ...

, who was a "staller", a standard-bearer and representative of the king (see Privileges section).

This fort was apparently rebuilt after the 1066 Norman Conquest

The Norman Conquest (or the Conquest) was the 11th-century invasion and occupation of England by an army made up of thousands of Norman, Breton, Flemish, and French troops, all led by the Duke of Normandy, later styled William the Conque ...

of England by Ralph Baynard, a follower of William the Conqueror

William I; ang, WillelmI (Bates ''William the Conqueror'' p. 33– 9 September 1087), usually known as William the Conqueror and sometimes William the Bastard, was the first House of Normandy, Norman List of English monarchs#House of Norman ...

and Sheriff of Essex

The High Sheriff of Essex was an ancient sheriff title originating in the time of the Angles, not long after the invasion of the Kingdom of England, which was in existence for around a thousand years. On 1 April 1974, under the provisions of the ...

. It was on the river-bank inside the Roman walls; a second Norman fort, Montfichet's Tower

Montfichet's Tower (also known as Montfichet's Castle and/or spelt Mountfitchet's or Mountfiquit's) was a Norman fortress on Ludgate Hill in London, between where St Paul's Cathedral and City Thameslink railway station now stand. First documen ...

, stood to the north.

The site of Baynard's Castle was adjacent to the church of St Andrew-by-the-Wardrobe, on the southern side of today's 160 Queen Victoria Street (the former ''Times'' office and now The Bank of New York Mellon

The Bank of New York Mellon Corporation, commonly known as BNY Mellon, is an American investment banking services holding company headquartered in New York City. BNY Mellon was formed from the merger of The Bank of New York and the Mellon Financ ...

Centre); archaeologists have found fortifications stretching at least south, onto the site of the proposed development at 2 Puddle Dock. This may be the ''Bainiardus'' mentioned in the Domesday Book

Domesday Book () – the Middle English spelling of "Doomsday Book" – is a manuscript record of the "Great Survey" of much of England and parts of Wales completed in 1086 by order of King William I, known as William the Conqueror. The manusc ...

of 1086 who gave his name to springs near Paddington

Paddington is an area within the City of Westminster, in Central London. First a medieval parish then a metropolitan borough, it was integrated with Westminster and Greater London in 1965. Three important landmarks of the district are Paddi ...

called Baynard's Watering, later shortened to Bayswater.

The castle was inherited by Ralph Baynard's son Geoffrey and his grandson William Baynard, but the latter forfeited his lands early in the reign of Henry I Henry I may refer to:

876–1366

* Henry I the Fowler, King of Germany (876–936)

* Henry I, Duke of Bavaria (died 955)

* Henry I of Austria, Margrave of Austria (died 1018)

* Henry I of France (1008–1060)

* Henry I the Long, Margrave of the ...

(1100–1135) for having supported Henry's brother Robert Curthose

Robert Curthose, or Robert II of Normandy ( 1051 – 3 February 1134, french: Robert Courteheuse / Robert II de Normandie), was the eldest son of William the Conqueror and succeeded his father as Duke of Normandy in 1087, reigning until 1106. ...

in his claim to the throne.Page (1923), p. 139 After a few years in the hands of the king, the castle passed to Eustace, Count of Boulogne, by 1106. John Stow gives 1111 as the date of forfeiture. Stow is an important source for the medieval history of London, but his dates in particular are not always reliable.

Later in Henry's reign, the feudal barony of Little Dunmow

Little Dunmow is a village situated in rural Essex, England, in the vale of the River Chelmer about east-southeast of the town of Great Dunmow. It can be reached from the Dunmow South exit of the A120 by following the road towards Braintree (B ...

and the soke of Baynard's Castle were granted to the king's steward, Robert Fitz Richard

__NOTOC__

Robert Fitz Richard (1064–1136) was an Anglo-Norman feudal baron of Little Dunmow, Essex and constable of Baynard's Castle in the City of London. His feudal barony, the caput of which was at Little Dunmow in Essex, was granted to hi ...

(1064–1136), younger son of Richard FitzGilbert de Clare (d. 1090), 1st feudal baron of Clare in Suffolk, near Dunmow. The soke was coterminous with the parish of St Andrew-by-the-Wardrobe, which was adjacent to the Norman castle; the soke roughly corresponds to the present Castle Baynard

Castle Baynard is one of the 25 wards of the City of London, the historic and financial centre of London.

Features

The ward covers an irregularly shaped area, sometimes likened to a tuning fork, bounded on the east by the wards of Queenhith ...

ward of the City of London. Both Little Dunmow and Baynard's Castle were eventually inherited by his grandson, Robert Fitzwalter

Robert FitzwalterAlso spelled Fitzwater, FitzWalter, fitzWalter, etc. (died 9 December 1235) was one of the leaders of the baronial opposition against King John, and one of the twenty-five sureties of ''Magna Carta''. He was feudal baron of Lit ...

(d. 1234).Stow (1598), pp. 269–283. Kingsford (1908)'notes

on Stow's text.

Fitzwalter and the barons' revolt

Fitzwalter was the leader of the barons' revolt against KingJohn

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Secon ...

, which culminated in the Magna Carta

(Medieval Latin for "Great Charter of Freedoms"), commonly called (also ''Magna Charta''; "Great Charter"), is a royal charter of rights agreed to by King John of England at Runnymede, near Windsor, on 15 June 1215. First drafted by the ...

of 1215. The ''Chronicle of Dunmow'' relates that King John desired Fitzwalter's daughter, Matilda the Fair (also known as Maid Marian Fitzwalter—the real-life Maid Marian

Maid Marian is the heroine of the Robin Hood legend in English folklore, often taken to be his lover. She is not mentioned in the early, medieval versions of the legend, but was the subject of at least two plays by 1600. Her history and circums ...

of the legend of Robin Hood

Robin Hood is a legendary heroic outlaw originally depicted in English folklore and subsequently featured in literature and film. According to legend, he was a highly skilled archer and swordsman. In some versions of the legend, he is depic ...

) and Fitzwalter was forced to take up arms to defend the honour of his daughter.

This romantic tale may well be propaganda giving legitimacy to a rebellion prompted by Fitzwalter's reluctance to pay tax or some other dispute. He plotted with the Welsh prince Llywelyn ab Iorwerth

Llywelyn the Great ( cy, Llywelyn Fawr, ; full name Llywelyn mab Iorwerth; c. 117311 April 1240) was a King of Gwynedd in north Wales and eventually " Prince of the Welsh" (in 1228) and "Prince of Wales" (in 1240). By a combination of war and d ...

and Eustace de Vesci

Eustace de Vesci (1169–1216) was an English lord of Alnwick Castle, and a ''Magna Carta'' surety. He also held lands in Sprouston, Roxburghshire, Scotland as brother in-law to King Alexander II of Scotland. Eustace was a leader during the Baro ...

of Alnwick Castle

Alnwick Castle () is a castle and country house in Alnwick in the English county of Northumberland. It is the seat of the 12th Duke of Northumberland, built following the Norman conquest and renovated and remodelled a number of times. It is a G ...

in 1212. John got wind of the plot and exiled Fitzwalter and de Vesci, who fled to France and Scotland, respectively. On 14 January 1213 John destroyed Castle Baynard.

Fitzwalter was forgiven under the terms of the king's submission to Pope Innocent III

Pope Innocent III ( la, Innocentius III; 1160 or 1161 – 16 July 1216), born Lotario dei Conti di Segni (anglicized as Lothar of Segni), was the head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 8 January 1198 to his death in 16 J ...

in May 1213. His estates were restored on 19 July 1213 and according to Stow he was given licence to repair Castle Baynard and his other castles.

It is not clear to what extent the castle was rebuilt, but in 1275 Robert FitzWalter, 1st Baron FitzWalter

Robert FitzWalter, 1st Baron FitzWalter (1247 – 18 January 1326) was an English Peerage of England, peer.

Life

Robert Fitzwalter was the only son of Sir Walter FitzRobert of Woodham Walter, Essex (son of Robert Fitzwalter), and Ida II Longespé ...

(Fitzwalter's grandson), was given licence to sell the site to Robert Kilwardby

Robert Kilwardby ( c. 1215 – 11 September 1279) was an Archbishop of Canterbury in England and a cardinal. Kilwardby was the first member of a mendicant order to attain a high ecclesiastical office in the English Church.

Life

Kilwardby s ...

, Archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Canterbury. The current archbishop is Justi ...

, to serve as the precinct of the great Dominican Priory at Blackfriars Blackfriars, derived from Black Friars, a common name for the Dominican Order of friars, may refer to:

England

* Blackfriars, Bristol, a former priory in Bristol

* Blackfriars, Canterbury, a former monastery in Kent

* Blackfriars, Gloucester, a f ...

built in 1276. Montfichet's Tower was included in the sale, having also been destroyed by King John in 1213.

Building of the priory required a section of the City Wall to be repositioned and the former military functions of the castle were taken up by a new "tower" in the river at the end of the wall. Started under the great castle-builder King Edward I (1272–1307), it was completed during the reign of his son Edward II

Edward II (25 April 1284 – 21 September 1327), also called Edward of Caernarfon, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 1307 until he was deposed in January 1327. The fourth son of Edward I, Edward became the heir apparent to t ...

(1307–1327) and was demolished in 1502. This was probably the tower of "Legate's Inn" given by Edward III

Edward III (13 November 1312 – 21 June 1377), also known as Edward of Windsor before his accession, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from January 1327 until his death in 1377. He is noted for his military success and for restoring r ...

to William de Ros.

Privileges

The lord of Castle Baynard appears to have had held a special place among the nobility of London. Robert Fitzwalter explicitly retained all the franchises and privileges associated with the lordship of Baynard when he made the sale. He claimed them in 1303, his son Robert tried again before the King's Justices in 1327 and his brother John FitzWalter tried again in 1347 in front of the

The lord of Castle Baynard appears to have had held a special place among the nobility of London. Robert Fitzwalter explicitly retained all the franchises and privileges associated with the lordship of Baynard when he made the sale. He claimed them in 1303, his son Robert tried again before the King's Justices in 1327 and his brother John FitzWalter tried again in 1347 in front of the Lord Mayor of London

The Lord Mayor of London is the mayor of the City of London and the leader of the City of London Corporation. Within the City, the Lord Mayor is accorded precedence over all individuals except the sovereign and retains various traditional powe ...

and Common Council, all without success.

These law-suits centred on a claim to be the "Chief Banneret" of London. Created in the reign of Edward I (1272–1307), knights banneret

A knight banneret, sometimes known simply as banneret, was a medieval knight ("a commoner of rank") who led a company of troops during time of war under his own banner (which was square-shaped, in contrast to the tapering standard or the penno ...

led troops into battle under their own banner not that of a feudal superior. It seems that the tenure

Tenure is a category of academic appointment existing in some countries. A tenured post is an indefinite academic appointment that can be terminated only for cause or under extraordinary circumstances, such as financial exigency or program disco ...

of Castle Baynard had entitled FitzWalter's ancestors to carry the banner of the City of London

The City of London is a city, ceremonial county and local government district that contains the historic centre and constitutes, alongside Canary Wharf, the primary central business district (CBD) of London. It constituted most of London fr ...

, and hence be leaders of the London forces. In 1136 Robert Fitz Richard had claimed the "lordship of the Thames" from London to Staines, as the king's banner-bearer and as guardian of the whole City of London.Page (1923), p. 193

In times of peace, the soke of Castle Baynard held a court which sentenced criminals convicted before the Lord Mayor at the Guildhall

A guildhall, also known as a "guild hall" or "guild house", is a historical building originally used for tax collecting by municipalities or merchants in Great Britain and the Low Countries. These buildings commonly become town halls and in som ...

, and maintained a prison and stocks.Page (1923), p. 191 Traitors were tied to a post at Wood Wharf and were drowned as the tide overwhelmed them. Fitzwalter was invited to the Court of Privilege, held at the Great Council in the Guildhall, sitting next to the Lord Mayor making pronouncements of all judgments. This may represent a combination of the post-Conquest Anglo-Norman roles of feudal constable

A constable is a person holding a particular office, most commonly in criminal law enforcement. The office of constable can vary significantly in different jurisdictions. A constable is commonly the rank of an officer within the police. Other peop ...

and local justiciar with the ancient Anglo-Saxon office of ''staller''. The latter was the king's standard-bearer in war who was his spokesman at the Danish ''thing

Thing or The Thing may refer to:

Philosophy

* An object

* Broadly, an entity

* Thing-in-itself (or ''noumenon''), the reality that underlies perceptions, a term coined by Immanuel Kant

* Thing theory, a branch of critical theory that focuse ...

'', the 11th-century governing assembly.

New site

A "Hospice called le Old Inne by Pauls Wharfe" is listed in the possessions ofEdward of Norwich, 2nd Duke of York

Edward, 2nd Duke of York, ( – 25 October 1415) was an English nobleman, military commander and magnate. He was the eldest son of Edmund of Langley, 1st Duke of York, and a grandson of King Edward III of England. He held significant appointment ...

, who was killed at the Battle of Agincourt

The Battle of Agincourt ( ; french: Azincourt ) was an English victory in the Hundred Years' War. It took place on 25 October 1415 (Saint Crispin's Day) near Azincourt, in northern France. The unexpected English victory against the numerica ...

in 1415. He may have acquired the house by his marriage to Philippa de Mohun

Philippa de Mohun (c. 1367 – 17 July 1431) was Duchess of York, as a result of her third marriage to Edward of Norwich, 2nd Duke of York (c.1373–1415), Lord of the Isle of Wight, a grandson of King Edward III (1327–1377). She succeeded h ...

, widow of Walter Fitzwalter (d. 1386).

A declaration of 1446 appears to identify this building with a town-house built on land reclaimed from the river, south-east of the original castle. Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester

Humphrey of Lancaster, Duke of Gloucester (3 October 139023 February 1447) was an English prince, soldier, and literary patron. He was (as he styled himself) "son, brother and uncle of kings", being the fourth and youngest son of Henry IV of E ...

, rebuilt the house after a "great fire" in 1428, with four wings in a trapezoid

A quadrilateral with at least one pair of parallel sides is called a trapezoid () in American and Canadian English. In British and other forms of English, it is called a trapezium ().

A trapezoid is necessarily a Convex polygon, convex quadri ...

al shape around a courtyard. Excavations have shown that the Roman riverside wall, on the south side of the medieval Thames Street, formed the foundation of the north wall of the new house. It seems that the nearby waterfront was known as Baynard's Castle even after the original castle was destroyed, and the name was transferred to the building on the new site.

Gloucester died within days of being arrested for treason in 1447. The house was forfeited to the crown before being occupied at some time before 1457 by Edward's nephew Richard Plantagenet, 3rd Duke of York, the former Lord Protector, who kept 400 gentlemen and men-at-arms at the castle in his pursuit of his claim to the throne; he was killed at the Battle of Wakefield in 1460.

This London powerbase allowed York's son to be crowned as King Edward IV in the great hall of the castle, whilst Henry VI and Margaret of Anjou were campaigning in northern England. Edward gave the castle to his mother Cecily Neville

Cecily Neville (3 May 1415 – 31 May 1495) was an English noblewoman, the wife of Richard, Duke of York (1411–1460), and the mother of two kings of England— Edward IV and Richard III. Cecily Neville was known as "the Rose of Raby", beca ...

on 1 June 1461, a few weeks before his coronation, and he housed his family there for safety before the decisive Battle of Barnet

The Battle of Barnet was a decisive engagement in the Wars of the Roses, a dynastic conflict of 15th-century England. The military action, along with the subsequent Battle of Tewkesbury, secured the throne for Edward IV. On Sunday 14 April ...

.

After the young princes Edward V and his brother Richard

Richard is a male given name. It originates, via Old French, from Frankish language, Old Frankish and is a Compound (linguistics), compound of the words descending from Proto-Germanic language, Proto-Germanic ''*rīk-'' 'ruler, leader, king' an ...

were declared illegitimate in 1483 and imprisoned in the Tower of London, Edward's brother was crowned as King Richard III

Richard III (2 October 145222 August 1485) was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 26 June 1483 until his death in 1485. He was the last king of the House of York and the last of the Plantagenet dynasty. His defeat and death at the Battl ...

at Baynard's Castle, as recounted in Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

's play ''Richard III''.

Tudors

In 1501 King Henry VII "repayred or rather new builded this house, not imbattoled, or so strongly fortified castle like, but farre more beautiful and commodious for the entertainement of any prince or greate estate" (Stow). Henry's alterations included five projecting towers between two existing polygonal corner towers on the river-front. Henry stayed at the castle when attending functions at

In 1501 King Henry VII "repayred or rather new builded this house, not imbattoled, or so strongly fortified castle like, but farre more beautiful and commodious for the entertainement of any prince or greate estate" (Stow). Henry's alterations included five projecting towers between two existing polygonal corner towers on the river-front. Henry stayed at the castle when attending functions at St Paul's Cathedral

St Paul's Cathedral is an Anglican cathedral in London and is the seat of the Bishop of London. The cathedral serves as the mother church of the Diocese of London. It is on Ludgate Hill at the highest point of the City of London and is a Grad ...

. His son Henry VIII gave the castle to his first wife Catherine of Aragon

Catherine of Aragon (also spelt as Katherine, ; 16 December 1485 – 7 January 1536) was Queen of England as the first wife of King Henry VIII from their marriage on 11 June 1509 until their annulment on 23 May 1533. She was previously ...

on 10 June 1509, the day before their wedding, and the queen took up residence there. Margaret Tudor

Margaret Tudor (28 November 1489 – 18 October 1541) was Queen of Scotland from 1503 until 1513 by marriage to King James IV. She then served as regent of Scotland during her son's minority, and successfully fought to extend her regency. Marg ...

, widow of James IV of Scotland, came to stay at Baynard's Castle in May 1516. Later one of Henry's favourite courtiers, Sir William Sidney

Sir William Sidney (1482?–1554) was an English courtier under Henry VIII and Edward VI.

Life

He was eldest son of Nicholas Sidney, by Anne, sister of Sir William Brandon. In 1511 he accompanied Thomas Darcy, 1st Baron Darcy de Darcy into Spa ...

(c.1482–1554), tutor to his son the future Edward VI

Edward VI (12 October 1537 – 6 July 1553) was King of England and Ireland from 28 January 1547 until his death in 1553. He was crowned on 20 February 1547 at the age of nine. Edward was the son of Henry VIII and Jane Seymour and the first E ...

, lived in the castle and made his will there in 1548.

By 1551 the house had passed to William Herbert, 1st Earl of Pembroke (1501–1570), the year in which that influential courtier was created Earl of Pembroke

Earl of Pembroke is a title in the Peerage of England that was first created in the 12th century by King Stephen of England. The title, which is associated with Pembroke, Pembrokeshire in West Wales, has been recreated ten times from its origin ...

. It was at Baynard's Castle that the Privy Council

A privy council is a body that advises the head of state of a state, typically, but not always, in the context of a monarchic government. The word "privy" means "private" or "secret"; thus, a privy council was originally a committee of the mon ...

met to end the claim of Lady Jane Grey

Lady Jane Grey ( 1537 – 12 February 1554), later known as Lady Jane Dudley (after her marriage) and as the "Nine Days' Queen", was an English noblewoman who claimed the throne of England and Ireland from 10 July until 19 July 1553.

Jane was ...

to the throne and proclaim Mary

Mary may refer to:

People

* Mary (name), a feminine given name (includes a list of people with the name)

Religious contexts

* New Testament people named Mary, overview article linking to many of those below

* Mary, mother of Jesus, also calle ...

as Queen of England. Pembroke's wife Anne Parr (sister of Queen Catherine Parr

Catherine Parr (sometimes alternatively spelled Katherine, Katheryn, Kateryn, or Katharine; 1512 – 5 September 1548) was Queen of England and Ireland as the last of the six wives of King Henry VIII from their marriage on 12 July 1543 until ...

, widow of Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is best known for his six marriages, and for his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disa ...

) died in the castle in 1552. The house was extended to the west in about 1550 with three wings of brick, faced with stone on the river-front. The second courtyard formed by this extension is clearly visible on Hollar's view of London before the Great Fire. Old prints show a large gateway in the middle of the south side, a bridge of two arches and steps down to the river.

The house remained in the Herbert family until the death of Philip Herbert, 4th Earl of Pembroke, Chancellor of the University of Oxford

This is a list of chancellors of the University of Oxford in England by year of appointment.

__TOC__

Chronological list

See also

* List of vice-chancellors of the University of Oxford

*List of University of Oxford people

* List of chancell ...

. He preferred to live at Whitehall Palace

The Palace of Whitehall (also spelt White Hall) at Westminster was the main residence of the English monarchs from 1530 until 1698, when most of its structures, except notably Inigo Jones's Banqueting House of 1622, were destroyed by fire. Hen ...

while his wife Anne Clifford

Lady Anne Clifford, Countess of Dorset, Pembroke and Montgomery, ''suo jure'' 14th Baroness de Clifford (30 January 1590 – 22 March 1676) was an English peeress. In 1605 she inherited her father's ancient barony by writ and became ''suo jure'' ...

(1590–1676) took up residence in Baynard's Castle, describing it in her memoirs as "a house full of riches, and more secured by my lying there". The 4th Earl sided with the Parliamentarians in the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

and died in 1650. By 1660 and the Restoration of the Monarchy, the house was occupied by Francis Talbot, 11th Earl of Shrewsbury

Francis Talbot, 11th Earl of Shrewsbury, 11th Earl of Waterford (1623 – 16 March 1668), was an English peer who was a Royalist officer in the English Civil War. He survived the war only to be mortally wounded in a duel with the Duke of Bucking ...

, who had fought on the side of the Royalist

A royalist supports a particular monarch as head of state for a particular kingdom, or of a particular dynastic claim. In the abstract, this position is royalism. It is distinct from monarchism, which advocates a monarchical system of governme ...

army in their defeat at the Battle of Worcester

The Battle of Worcester took place on 3 September 1651 in and around the city of Worcester, England and was the last major battle of the 1639 to 1653 Wars of the Three Kingdoms. A Parliamentarian army of around 28,000 under Oliver Cromwell d ...

in 1651. Samuel Pepys records that on 19 June 1660 "My Lord (i.e. his relative Edward Montagu) went at night with the King to Baynard's Castle to supper ... he next morning helay long in bed this day, because he came home late from supper with the King".

After the Great Fire

Baynard's Castle was destroyed in the

Baynard's Castle was destroyed in the Great Fire of London

The Great Fire of London was a major conflagration that swept through central London from Sunday 2 September to Thursday 6 September 1666, gutting the medieval City of London inside the old Roman city wall, while also extending past the ...

of 1666. The engraver Wenceslaus Hollar

Wenceslaus Hollar (23 July 1607 – 25 March 1677) was a prolific and accomplished Bohemian graphic artist of the 17th century, who spent much of his life in England. He is known to German speakers as ; and to Czech speakers as . He is particu ...

depicted considerable ruins standing after the fire, including the stone facade on the river side, but only a round tower was left when Strype was writing in 1720. This tower had been converted into a dwelling, whilst the rest of the site became timber

Lumber is wood that has been processed into dimensional lumber, including beams and planks or boards, a stage in the process of wood production. Lumber is mainly used for construction framing, as well as finishing (floors, wall panels, wi ...

yards and wood wharves

A wharf, quay (, also ), staith, or staithe is a structure on the shore of a harbour or on the bank of a river or canal where ships may dock to load and unload cargo or passengers. Such a structure includes one or more berths (mooring location ...

with Dunghill Lane running through the site from Thames Street. Richard Horwood's map of c. 1813 shows a wharf which in 1878 belonged to the Castle Baynard Copper Company. The remaining tower (some sources say two survived) was pulled down in the 19th century to make way for warehouses of the Carron Company

The Carron Company was an ironworks established in 1759 on the banks of the River Carron near Falkirk, in Stirlingshire, Scotland. After initial problems, the company was at the forefront of the Industrial Revolution in the United Kingdom. T ...

.

In the 1970s the area was redeveloped, with the construction of the Blackfriars underpass and a Brutalist office block named " Baynard House", occupied by the telephone company

In the 1970s the area was redeveloped, with the construction of the Blackfriars underpass and a Brutalist office block named " Baynard House", occupied by the telephone company BT Group

BT Group plc (trading as BT and formerly British Telecom) is a British multinational telecommunications holding company headquartered in London, England. It has operations in around 180 countries and is the largest provider of fixed-line, broa ...

. Most of the site under Baynard House is a scheduled monument

In the United Kingdom, a scheduled monument is a nationally important archaeological site or historic building, given protection against unauthorised change.

The various pieces of legislation that legally protect heritage assets from damage and d ...

.

Archaeology

Most of the archaeological evidence for the second Baynard's Castle comes from excavations in 1972–5, before the construction of Baynard House office block. Parts of the north wing of both the original house and extension were found, including the north gate and gatetower, and the cobbled entrance from Thames Street.Jackson (2009ii) p. 25 Two east–west "limestone" walls were found; the excavator suggested that the more northerly one was the curtain wall of the pre-1428 castle, and the other was a post-1428 replacement. The latter was surmounted by a brick facing with a rubble core, to which a rectangular pier was attached. The castle had foundations of chalk,ragstone

Rag-stone is a name given by some architectural writers to work done with stones that are quarried in thin pieces, such as Horsham Stone, sandstone, Yorkshire stone, and the slate stones, but this is more properly flag or slab work. Near London ...

and mortar and was built entirely on reclaimed land. Several phases of building in the late 17th century were also identified. Excavations in 1981 at the City of London School uncovered the SE corner tower of the Tudor castle. The London Archaeological Archive codes for the excavations are BC72/GM152, UT74, BC74, BC75 and BYD81.Jackson (2009ii) pp. 25, 28–9, seLondon Archaeological Archive

for more details of excavations.

See also

*Fortifications of London

The fortifications of London are extensive and mostly well maintained, though many of the City of London's fortifications and defences were dismantled in the 17th and 18th century. Many of those that remain are tourist attractions, most notably th ...

* Montfichet's Tower

Montfichet's Tower (also known as Montfichet's Castle and/or spelt Mountfitchet's or Mountfiquit's) was a Norman fortress on Ludgate Hill in London, between where St Paul's Cathedral and City Thameslink railway station now stand. First documen ...

– Norman castle on Ludgate Hill

* Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, which is separa ...

Notes

References

Further reading

* * * {{coord , 51, 30, 41, N, 0, 6, 0, W, type:landmark_region:GB-LND, display=title Former buildings and structures in the City of London Royal buildings in London Castles in London